Well, I was on the road for 1.5 days (work party for the Community Village at the Oregon Country Fair). As I was driving home, there was a magnitude M 5.6 earthquake in coastal northern California. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/nc73201181/executive I didn’t realize…

Earthquake Report: Mendocino fault! (northern California)

I was driving around Eureka today, running to the appliance center to get an appliance (heheh). I got a message from a long time held friend (who lives in Salinas, CA). They asked me if I was OK, given that…

Earthquake Report: Philippines

I put these together earlier this week for my classes and finally have a moment to write about these earthquakes. The Philippines region has been quite active lately, as it frequently is. I show below a series of earthquakes from…

Earthquake Report: Botswana!

This is a very interesting M 6.5 earthquake, which was preceded by a probably unrelated M 5.2 earthquake. Last September, there was an M 5.7 earthquake in Tanzania along the western shores of Lake Victoria. Here is my report for…

Earthquake Report: Kamchatka!

This earthquake happened last night as I was preparing course materials for this morning. Initially it was a magnitude 6.9, but later modified to be M 6.9. This earthquake happened in an interesting region of the world where there is…

Good Friday Earthquake 27 March 1964

In March of 1964, plate tectonics was still a hotly debated topic at scientific meetings worldwide. Some people still do not accept this theory (some Russian geologists favor alternative hypotheses; Shevchenko et al., 2006). At the time, there was some…

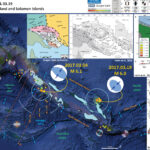

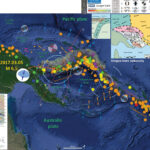

Earthquake Report: Bougainville and Solomons

In the past couple of weeks, there were some earthquakes in the equatorial western Pacific. Here are the USGS websites for the two largest earthquakes in the two regions. 2017.03.04 M 6.1 2017.03.19 M 6.0 The M 6.1 was a…

Earthquake Report: New Britain

We just had an earthquake with a USGS magnitude of M 6.5 along the subduction zone formed by the convergence of the Solomon Sea plate on the south and the South Bismarck plate on the north. Here is the USGS…

Earthquake Report: Banda Sea

Earlier this week there was a moderate earthquake along a strike-slip fault that appears to adjoin the Banda/Timor/Java Arc with New Guinea. This strike-slip fault appears to cross oblique to the subduction zone that forms the Timor Trench to the…

Earthquake Report: Alaska

We had an earthquake a few days ago along the Cook Strait west of Anchorage, Alaska. This earthquake happened nearby a couple earthquakes from the past 2 years that have similar senses of motion along faults that seem to be…