While I was travelling back from a USGS Powell Center Workshop on the recurrence of earthquakes along the Cascadia subduction zone, there was an earthquake (gempa) offshore of Sumatra. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us7000iqpn/executive There was actually a foreshock (more than one): https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us7000iq2d/executive I…

Earthquake Report: M 6.2 along the Great Sumatra fault

There was a magnitude M 6.2 Gempa or Earthquake on 25 February 2022. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us6000gzyg/executive The plate boundary fault system that dominates the tectonics of the Island of Sumatera, Indonesia, is the complicated. The oceanic India-Australia plate converges with the Eurasia…

Earthquake Report: Mentawai, Sumatra

We just had an earthquake in the Mentawai region of the Sunda subduction zone offshore of Sumatra. Here is the USGS website for this M 6.3 earthquake. Based upon the hypocentral depth and the current estimate of the location of…

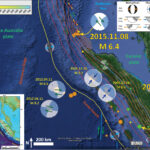

Earthquake Report: Bengkulu (Sumatra)!

Last night (my time) while I was tending to other business, there was an earthquake along the Sunda Megathrust. Here is the USGS website for this M 6.4 earthquake. This M 6.4 earthquake happened down-dip (“deeper than”) along the megathrust…

Earthquake Report: Sumatra!

There were two interesting earthquakes near the northern tip of the Island of Sumatra whilst I was off on a field trip with some HSU geology students. So, I think it prudent to review these earthquakes now. These earthquakes happened…

Earthquake Anniversary: Sumatra-Andaman 2004 M 9.2 & 2005 M 8.6

On 26 December 2004 there was an earthquake with a magnitude of M 9.2 along the Sumatra-Andaman subduction zone (SASZ). This earthquake is the third largest earthquake ever recorded by modern seismometers and ruptured nearly 2,000 km of the megathrust…

Earthquake Report: Java Sea!

Last night as I was finishing work for the day, I noticed an earthquake in the Java Sea, just north of western Java. Here is the USGS website for this M 6.6 earthquake. This earthquake is extensional and plots very…

Earthquake Report: Burma!

Well, there was an earthquake about 6 hours ago in Burma. This M 6.8 earthquake was rather deep, which is good for the residents of that area (the ground motions diminish with distance from the earthquake hypocenter). Here is the…

Earthquake Report: Sumatra!

We just had a M = 7.8 earthquake southwest of the Island of Sumatra, a volcanic arc formed from the subduction of the India-Australia plate beneath the Sunda plate (part of Eurasia). Here is the USGS website for this earthquake.…

Earthquake Report: Nicobar Isles and Sumatra!

This past 24 hours include two large earthquakes in the region of the Sumatra-Andaman subduction zone offshore of Sumatra. Here is a map using the USGS online GIS interface. Here are the two large earthquakes posted on the USGS websites:…