The other evening (my time) I and many others noticed a series of earthquakes in the Banda Sea region. As is typical, people want as much information about these earthquakes as possible as soon as possible. There were two quakes…

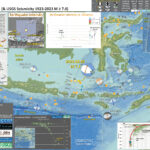

Earthquake Report: M 7.1 Indonesia

Yesterday on my way home from a Phil & Graham Lesh show, I got a tsunami notification alert from the National Tsunami Warning Center. There was a magnitude M 6.9 earthquake offshore of Indonesia and there was no tsunami threat…

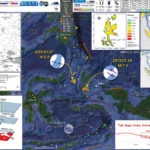

Earthquake Report: Banda Sea

Early morning (my time) there was an intermediate depth earthquake in the Banda Sea. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us70009b14/executive This earthquake was a strike-slip earthquake in the Australia plate. There are analogical earthquakes in the same area in 1963, 1987, 2005, and 2012 that…

Earthquake Report: Halmahera, Indonesia

Well, yesterday I was preparing some updates to the Ridgecrest Earthquake following my field work with my colleagues at the California Geological Survey (where I work) and the U.S. Geological Survey. We spent the week documenting surface ruptures associated with…

Earthquake Report: Indonesia

I had been making an update to an earthquake report on a regionally experienced M 5.6 earthquake from coastal northern California when I noticed that there was a M 7.3 earthquake in eastern Indonesia. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us600044zz/executive This earthquake is in a…

Earthquake Report: Sulawesi, Indonesia

Today I awoke to the USGS earthquake notification service email about an earthquake offshore of Sulawesi, Indonesia. There was an earthquake with a magnitude M 6.8 to the southeast of the Donggala/Palu earthquake from 28 September 2018. Here is the…

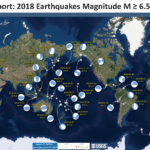

Earthquake Report: 2018 Summary

Here I summarize Earth’s significant seismicity for 2018. I limit this summary to earthquakes with magnitude greater than or equal to M 6.5. I am sure that there is a possibility that your favorite earthquake is not included in this…

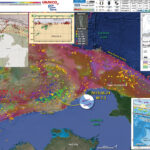

Earthquake/Landslide/Tsunami Report: Donggala Earthquake, Central Sulawesi: UPDATE #1

We continue to learn more each day as people collect additional information. Here is my initial Earthquake Report for this M 7.5 Donggala Earthquake. In short, there was an earthquake with magnitude M = 7.5 on 2018.09.28. Minutes after the…

Earthquake Report: Sulawesi (Celebes), Indonesia

Well, around 3 AM my time (northeastern Pacific, northern CA) there was a sequence of earthquakes including a mainshock with a magnitude M = 7.5. This earthquake happened in a highly populated region of Indonesia. This area of Indonesia is…

Earthquake Report: Lombok, Indonesia

Well well. After a pretty seismically quiet first half of 2018, we have been catching up rapidly. The ultra deep Great Earthquake in Fiji. And now the Lombok sequence continues. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us1000gda5/executive The inhabitants and tourists in the Lombok, Indonesia region…