Initial Narrative Well, it has been a very busy week. I had gotten back from the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in Chicago late Saturday night. I had one day to hang out with my cats before I was to…

Earthquake Report: Gorda Rise

It was a busy week (usual, right?). The previous week I was working on getting a house remodel done so someone could move in (they have been sleeping on couches for 6 months, so want to get them in asap).…

Earthquake Report: Mendocino triple junction

Well, it was a big mag 5 day today, two magnitude 5+ earthquakes in the western USA on faults related to the same plate boundary! Crazy, right? The same plate boundary, about 800 miles away from each other, and their…

Earthquake Report: Salt Lake City

As I was waking up this morning, I rolled over to check my social media feed and moments earlier there was a good sized shaker in Salt Lake City, Utah. I immediately thought of my good friend Jennifer G. who…

Earthquake Report: Mendocino fault

I was in Humboldt County last week for the Redwood Coast Tsunami Work Group meeting. I stayed there working on my house that a previous tenant had left in quite a destroyed state (they moved in as friends of mine).…

Earthquake Report: Gorda plate

On 10 February 2010 there was an earthquake with a magnitude of M 6.5, within the Gorda plate. This event was feld widely in the region, as well as statewide. In Humboldt County, we even made t-shirts about this quake.…

Earthquake Report: Mendocino triple junction

Well, I was on the road for 1.5 days (work party for the Community Village at the Oregon Country Fair). As I was driving home, there was a magnitude M 5.6 earthquake in coastal northern California. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/nc73201181/executive I didn’t realize…

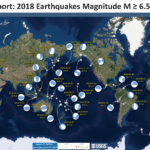

Earthquake Report: 2018 Summary

Here I summarize Earth’s significant seismicity for 2018. I limit this summary to earthquakes with magnitude greater than or equal to M 6.5. I am sure that there is a possibility that your favorite earthquake is not included in this…

Earthquake Report: Explorer plate

Last night I had completed preparing for class the next day. I was about to head to bed. I got an email from the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center notifying me that there was no risk of a tsunami due to…

Earthquake Report: Blanco fracture zone

As I was getting ready for school today, I noticed the M 6.2 notification from the USGS Earthquake Notification Service. People can sign up for the USGS ENS so that they can get emails when the USGS broadcasts this information.…