Well, yesterday was the start of a sequence of earthquakes offshore of San Clemente Island, about 100 km west of San Diego, California. The primary tectonic player in southern CA is the Pacific – North America plate boundary fault, the…

18 April 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

Today is the anniversary of the 18 April 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. There are few direct observations (e.g. from seismometers or other instruments) from this earthquake, so our knowledge of how strong the ground shook during the earthquake are limited…

Earthquake Report: Channel Islands Update #1

Well well. There was lots of interest in this M 5.3 earthquake offshore of Ventura/Los Angeles, justifiably so. Southern California is earthquake country. Here is an update. There was lots of information that I was trying to incorporate and I…

Earthquake Report: Channel Islands

I was finally getting around to writing a report for the deep Bolivia earthquake (Bolivia report here), when a M 5.3 earthquake struck offshore of the channel islands (south of Santa Cruz Island, west of Los Angeles). As is typical…

Earthquake Report: 1971 Sylmar, CA

This earthquake was the second earthquake in the state of CA to lead to major changes in how people in the state handled earthquake hazards and risk and today is the 47th anniversary of this earthquake. The first important earthquake…

Earthquake Report: Berkeley, CA (Hayward fault)

There was an earthquake last night (local time) in Berkeley, aligned with the Hayward fault. The Hayward fault is one of the synthetic sister faults to the San Andreas fault, the major player in the dextral (right-lateral, strike-slip) plate boundary…

Earthquake Report: Laytonville (northern CA)!

This morning there was a small earthquake in a region of northern California between two major faults that are part of the Pacific-North America plate boundary. The M 4.3 earthquake occurred between the San Andreas fault (SAF) to the west…

Earthquake Report: Trinidad, California

Early this morning, I was awakened by a mild jolt. I thought, well, seems like a M 3+- nearby. I did not get out of bed. The main shaking lasted a couple of seconds, though it seemed that there was…

Earthquake Report: 1992.04.25 M 7.2 Petrolia

The 25 April 1992 M 7.1 earthquake was a wake up call for many, like all large magnitude earthquakes are. I have some updated posters as of April 2021 (see below). Here is my personal story. I was driving my…

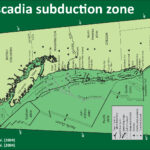

Earthquake Report: 1700 Cascadia subduction zone 317 year commemoration

Today (possibly tonight at about 9 PM) is the birthday of the last known Cascadia subduction zone (CSZ) earthquake. There is some evidence that there have been more recent CSZ earthquakes (e.g. late 19th century in southern OR / northern…