It was a busy week (usual, right?). The previous week I was working on getting a house remodel done so someone could move in (they have been sleeping on couches for 6 months, so want to get them in asap).…

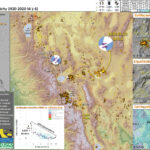

Earthquake Report: Mina Deflection in Nevada

I was slowly waking up while looking at my social media feed. moments before (maybe minutes) Anthony Lomax had posted his first motion earthquake mechanism for a M 6.4 near the CA/NV border. I leaped out of bed and got…

Earthquake Report: M 6.5 in Crete, Greece

Well, last weekend I was working on a house, so did not have the time to write this up until now. (2023 update: the magnitude is now M 6.5) https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us700098qd/executive The eastern Mediterranean Sea region is dominated by plate tectonics…

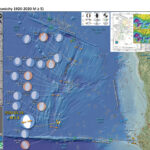

Earthquake Report: Banda Sea

Early morning (my time) there was an intermediate depth earthquake in the Banda Sea. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us70009b14/executive This earthquake was a strike-slip earthquake in the Australia plate. There are analogical earthquakes in the same area in 1963, 1987, 2005, and 2012 that…