Today I awoke to the USGS earthquake notification service email about an earthquake offshore of Sulawesi, Indonesia. There was an earthquake with a magnitude M 6.8 to the southeast of the Donggala/Palu earthquake from 28 September 2018. Here is the…

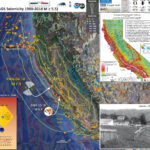

18 April 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

Today is the anniversary of the 18 April 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. There are few direct observations (e.g. from seismometers or other instruments) from this earthquake, so our knowledge of how strong the ground shook during the earthquake are limited…

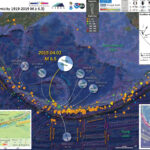

Earthquake Report: central Aleutians

A couple days ago, in my inbox, there was an email from the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center about an earthquake along the Aleutian Islands, near Rat Island, Alaska. However, this earthquake was not along the megathrust subduction zone fault there…