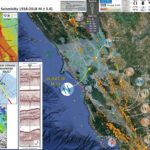

Well well. There was a small earthquake in the San Francisco Bay area today, with an epicenter in San Pablo Bay northwest of Richmond and San Pablo, CA. This earthquake is cool, at least in part, because of its location.…

Earthquake Report: Blanco fracture zone

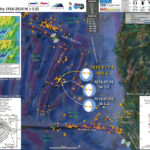

Well, so exciting to have more earthquakes to write about! This summer has been a low seismic summer. The entire year actually. There was an earthquake within the Gorda plate a few days ago, but these M 5.3 and M…

Earthquake Report: Lombok, Indonesia

Earlier today there was a shallow M 6.4 earthquake with an epicenter on the island of Lombok, Indonesia. With a hypocentral depth of about 7.5 km, this size of an earthquake can be quite damaging. The USGS PAGER estimate of…

#Earthquake Report: Gorda plate

Over the past night and morning, there was a sequence of earthquakes within the Gorda plate due west of Crescent City. Some people even felt these earthquakes, culminating (so far) with a M 5.6. There was a Gorda plate earthquake…