I don’t always have the time to write a proper Earthquake Report. However, I prepare interpretive posters for these events. Because of this, I present Earthquake Report Lite. (but it is more than just water, like the adult beverage that…

Earthquake Report: Cayman Islands

Contrary to what some people spread around on the internets (some of them major earthquake experts), strike-slip earthquakes can and do generate tsunami (just like this one). More on this below. I am in Portland, Oregon this week, attending the…

Earthquake Report: Puerto Rico!

Welcome to the next decade of the 21st century. We may look back a decade to review the second most deadly earthquake in the 21st century, from the magnitude M 7.0 Haiti Earthquake on 12 Jan 2010. I put together…

Earthquake Report: 2010 Haiti M 7.0

This is the ten year commemoration of the 2010 magnitude 7 earthquake in Haiti that caused widespread damage and casualties, triggered thousands of landslides, caused tsunami, triggered a turbidity current, and caused thousands to be internally displaced. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp000h60h/executive Here I…

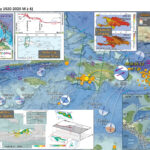

Earthquake Report: Guatemala and Mexico

This morning (my time) there was a moderately deep earthquake along the coast of southern Mexico and northern Guatemala. Here is my Temblor article about this M=6.6 earthquake and how it might relate to the 2017 M=8.2 quake. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us2000jbub/executive Offshore…

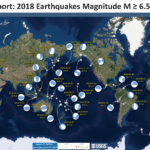

Earthquake Report: 2018 Summary

Here I summarize Earth’s significant seismicity for 2018. I limit this summary to earthquakes with magnitude greater than or equal to M 6.5. I am sure that there is a possibility that your favorite earthquake is not included in this…

Earthquake Report: Venezuela

Busy week! We just had a M 7.3 earthquake in northern Venezuela. Sadly, this large earthquake has the potential to be quite damaging to people and their belongings (buildings, infrastructure). https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us1000gez7/executive The northeastern part of Venezuela lies a large strike-slip…

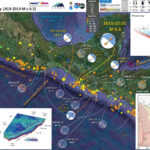

Earthquake Report: Cayman Trough!

Just a couple hours ago there was an earthquake along the Swan fault, which is the transform plate boundary between the North America and Caribbean plates. The Cayman trough (CT) is a region of oceanic crust, formed at the Mid-Cayman…

Earthquake Report: Guatemala

There was a fascinating earthquake sequence a few days ago on and offshore of Guatemala. Offshore of Guatemala in the Pacific Ocean, the Cocos plate subducts beneath the North America and Caribbean plates (NAP & CP). The transform plate boundary…