Here I summarize Earth’s significant seismicity for 2018. I limit this summary to earthquakes with magnitude greater than or equal to M 6.5. I am sure that there is a possibility that your favorite earthquake is not included in this…

Earthquake Report: Madagascar!

Today there was an earthquake in a region that we don’t hear about that often. Madagascar is off the coast of southeastern Africa and the oceanic basin to the west is likely formed as part of the East Africa Rift…

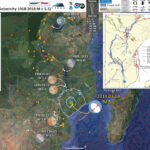

Earthquake Report: Malawi & Mozambique

Busy day today. This is my second earthquake report today. This report is about a M 5.6 earthquake along the Malawi Rift (MR) system, part of the larger East Africa Rift (EAR) extensional plate boundary. The EAR is currently the…

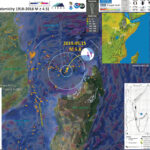

Earthquake Report: Botswana!

This is a very interesting M 6.5 earthquake, which was preceded by a probably unrelated M 5.2 earthquake. Last September, there was an M 5.7 earthquake in Tanzania along the western shores of Lake Victoria. Here is my report for…

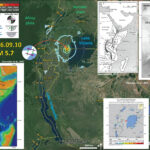

Earthquake Report: Tanzania

Well, I am a little late preparing this report. I actually put it together over the weekend, but am only now uploading this. There was an interesting earthquake along the southwestern edge of Lake Victoria, in the East-Africa Rift (EAR)…