I was in Humboldt County last week for the Redwood Coast Tsunami Work Group meeting. I stayed there working on my house that a previous tenant had left in quite a destroyed state (they moved in as friends of mine).…

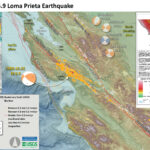

Earthquake Report: 1989 Loma Prieta!

Well, I prepared this report for the 30th anniversary of the 18 Oct 1989 Loma Prieta M 6.9 earthquake in central California, a.k.a. the World Series Earthquake (it happened during the 1989 World Series game at Candlestick Park in San…

Earthquake Report: Berkeley, CA (Hayward fault)

There was an earthquake last night (local time) in Berkeley, aligned with the Hayward fault. The Hayward fault is one of the synthetic sister faults to the San Andreas fault, the major player in the dextral (right-lateral, strike-slip) plate boundary…

San Francisco Bay: San Ramon Earthquake Swarm!

Those of you in the region of the San Francisco Bay are probably wondering what the likelihood that this recent and ongoing swarm of earthquakes in the San Ramon area may lead to a larger earthquake. I do not know,…

Small Earthquake in San Francisco Region

There was a M 3.6 earthquake near Concord, CA. This earthquake was felt widely across the S.F. Bay area. The two earthquakes plotted in the map below are both just southeast of the 2014 August Napa earthquake. The Napa earthquake,…