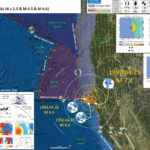

Well, so exciting to have more earthquakes to write about! This summer has been a low seismic summer. The entire year actually. There was an earthquake within the Gorda plate a few days ago, but these M 5.3 and M…

#Earthquake Report: Gorda plate

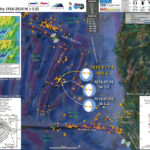

Over the past night and morning, there was a sequence of earthquakes within the Gorda plate due west of Crescent City. Some people even felt these earthquakes, culminating (so far) with a M 5.6. There was a Gorda plate earthquake…

Earthquake Report: Gorda plate!

I was at a workshop to develop a unified strategy for research and monitoring in the Klamath River estuary (led by the Yurok Tribe, Andreas Krauss) yesterday and missed feeling the first of two M 4.6-4.7 earthquakes. I was presenting…

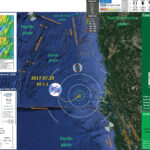

Earthquake Report: 2017 Cascadia Summary

Here I summarize the seismicity for Cascadia in 2017. I limit this summary to earthquakes with magnitude greater than or equal to M 2.5. I prepared reports for 6 of the 7 earthquakes presented (using moment tensors) on the main…

Earthquake Report: Mendocino fault! (northern California)

I was driving around Eureka today, running to the appliance center to get an appliance (heheh). I got a message from a long time held friend (who lives in Salinas, CA). They asked me if I was OK, given that…

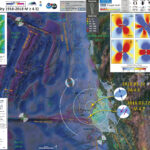

Earthquake Report: Gorda plate

We just had an earthquake in the Gorda plate. The USGS magnitude is 5.1. This earthquake happened a few kilometers southwest of the 2014 M 6.8 earthquake. Based upon the orientation of the faults in the region, today’s earthquake may…

Earthquake Report: Trinidad, California

Early this morning, I was awakened by a mild jolt. I thought, well, seems like a M 3+- nearby. I did not get out of bed. The main shaking lasted a couple of seconds, though it seemed that there was…

Earthquake Report: 1992.04.25 M 7.2 Petrolia

The 25 April 1992 M 7.1 earthquake was a wake up call for many, like all large magnitude earthquakes are. I have some updated posters as of April 2021 (see below). Here is my personal story. I was driving my…

Earthquake Report: 1700 Cascadia subduction zone 317 year commemoration

Today (possibly tonight at about 9 PM) is the birthday of the last known Cascadia subduction zone (CSZ) earthquake. There is some evidence that there have been more recent CSZ earthquakes (e.g. late 19th century in southern OR / northern…

Earthquake Report: Explorer plate!

In the past 2 days there have been a few earthquakes in the Explorer plate region along the Pacific-North America plate boundary. On March 19 of this year there was a series of earthquakes in this same region (to the…