Well, last weekend I was working on a house, so did not have the time to write this up until now. (2023 update: the magnitude is now M 6.5) https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us700098qd/executive The eastern Mediterranean Sea region is dominated by plate tectonics…

Earthquake Report: East Anatolia fault zone

This M 6.7 earthquake was the result of slip probably along a left-lateral strike-slip fault associated with the East Anatolia fault zone (EAF). The event was shallow and produced strong ground shaking in the region. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/us60007ewc/executive As I write this,…

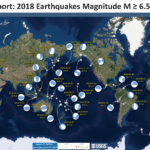

Earthquake Report: 2018 Summary

Here I summarize Earth’s significant seismicity for 2018. I limit this summary to earthquakes with magnitude greater than or equal to M 6.5. I am sure that there is a possibility that your favorite earthquake is not included in this…

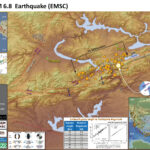

Earthquake Report: Greece

Well, I was about to head to town and noticed a magnitude M = 5.0 earthquake in Greece. I thought to myself, I wonder if that is a foreshock. It was. Then, the M 6.8 mainshock hit while i was…